Reading, Memory, and Migration (Article #10)

My mother-in-law introduced me to my husband’s Lithuanian heritage through a book. I set out to understand her reading journey from Lithuania to WWII refugee camps in Germany to life in America.

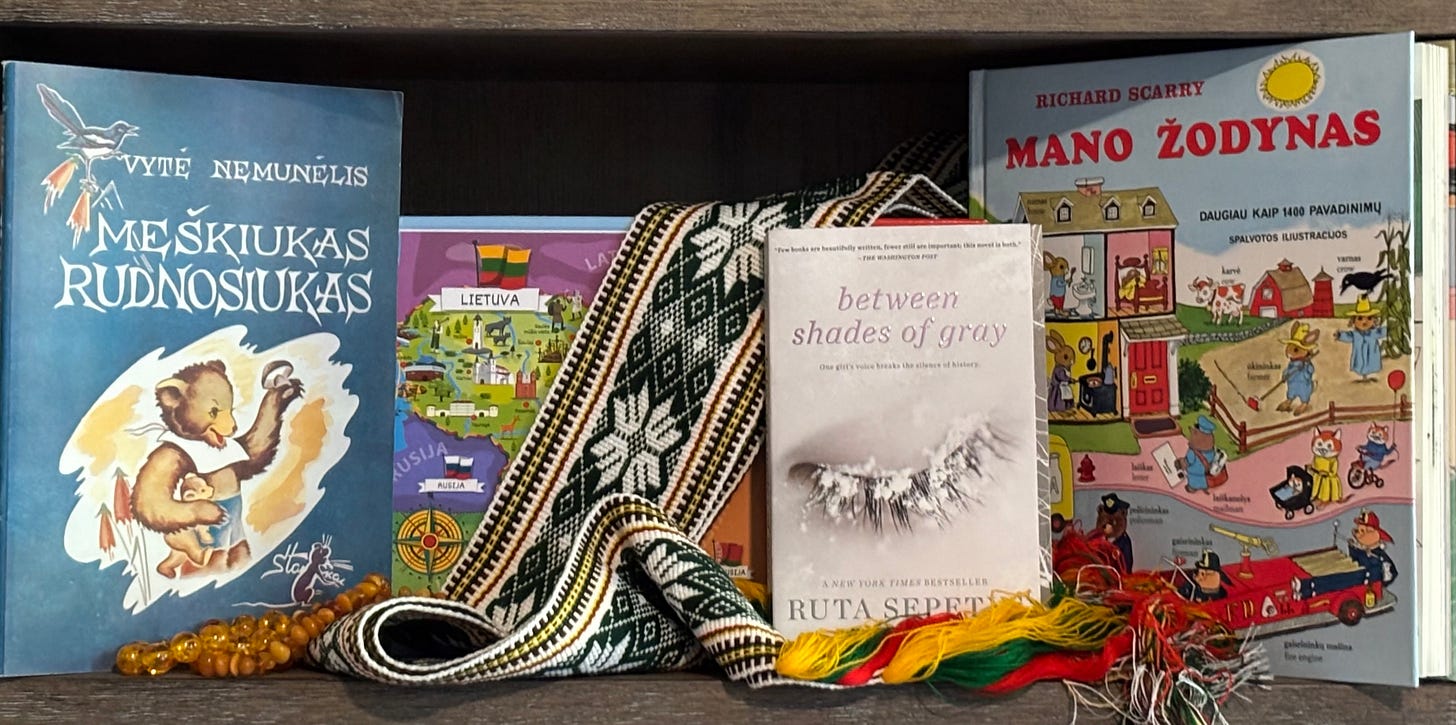

When my husband and I were still dating, my future mother-in-law and I quickly bonded over books. At one point, she gifted me the novel “Between Shades of Gray” by Ruta Sepetys, who I now consider one of my favorite authors.

In this historical fiction novel, when the Soviet Union invades Lithuania during WWII, 15-year-old Lina and her family are labeled as “anti-Soviet” because her parents are part of the educated class. As a result, they are deported from their home country to a Siberian labor camp where they struggle to survive the brutal conditions.

Before a similar fate befell my mother-in-law’s parents– her mother a grammar school teacher and her father a trained police officer– they fled.

“The war was coming closer to where [my parents] lived, so they decided to leave, and my father wanted to leave me on the farm with the grandparents, but my mother said, ‘No way!’, so they got a wagon and a horse and a neighbor who wanted to leave with them,” she recalled.

My mother-in-law was barely two when it happened. The family packed little. Her father suggested leaving her behind because they really did not anticipate being gone long.

They would spend the next five years in refugee camps in Munich, Germany.

My mother-in-law introduced me to my husband’s ancestral history through reading. In my Article #9 titled “What Is Your Family’s Reading Legacy?”, I explored my family’s history with reading and the impact it bears on my own daughter’s reading journey. Yet, I want her to know how her reading journey is influenced by her father’s side as well. Therefore, I set out to chat at length with my mother-in-law about her own reading experience.

I came to learn she takes a no-nonsense approach to the endeavor.

“How else will you know things if you don’t read?” she asked.

In fact, she expressed surprise when I shared that recent data is showing more and more young people aren’t reading.

“I thought everybody has to read,” she said.

When I asked if she instilled a love of reading in her own children, she answered with an immediate “No.”

That response came from a practical place of love.

“They better read or else.” She laughed. “Why wouldn’t they read? I never had that idea that you don’t have to read.”

She, herself, can’t fully articulate why she loves reading. She just does, she said, referring to it as her addiction.

With no computer or internet in the house, she ventures weekly to the three libraries in her radius, making bee-lines to the “New Books” section to see what catches her eye. She’s willing to try anything, giving it 100 pages before she decides whether or not to put it down in order to pick up something else.

She recently just read and returned the following:

The 2026 Old Farmer’s Almanac

The Miracle Book: A Simple Guide To Asking for the Impossible by Anthony DeStefano

Silence of the Gods: The Untold History of Europe’s Last Pagan Peoples by Francis Young

“See? I read all kinds of books that catch my eye– really! I’m not kidding,” she exclaimed with delight.

The last book listed also highlights my mother-in-law’s eagerness to learn more about the country she left behind.

“I want to read those because I left Lithuania in my mother’s arms. I want to know more about it,” she noted.

When she lived in Lithuanian refugee camps in Germany, she recalled get-togethers for the children or campfire gatherings where she learned the songs, legends and history of her homeland.

She’d continue to learn about Lithuania once her family emigrated to America after WWII. At the age of 7, my mother-in-law crossed the Atlantic on the USS General Haan, arriving in New Orleans.

She took out a manilla envelope, kept safely among her prized books in a cream-colored bookshelf, to show me a copy of the ship’s passenger log.

Once in America, her family would take a boat up the Mississippi River in order to catch a train to Chicago.

At Lithuanian schools in the States, my mother-in-law would continue to learn how to read and write Lithuanian while studying her heritage; she would learn to read and write English at Catholic grammar schools.

“I don’t know why my parents wanted to send [me to Catholic school]; it cost money for them, but they said that’s what they’ll do– give us a good education,” she said.

Originally, my mother-in-law was held back a year to learn the language. Once her parents saved enough money to buy a house in a new neighborhood with a new Catholic school, it was a nun there who encouraged her to work daily on her reading.

“The sister said I should read with someone every day after school, so I did [with] Aunt Nellie,” she recollected.

Aunt Nellie was the recently married daughter of a distant cousin who had sponsored my mother-in-law’s family upon their arrival to the States.

“Every day after school I walked to Aunt Nellie’s house, and I read,” she continued.

My mother-in-law wasn’t thrilled to be doing this, though.

“I was reading all the words in the book– maybe the book we had in school– and I was thinking, ‘Why am I here? It’s no big deal; I can read it.’ But, I was supposed to go by Aunt Nellie for about a year, every day, for a half hour after school,” she said.

And that’s what she did. From grade school into college, my mother-in-law studied because that was her parents’ expectation of her.

Her parents’ training in Lithuania and her father’s veterinarian degree from the University of Munich did not transfer to the U.S., and so, her parents took jobs in the factories– her father working during the day and her mother in the evenings.

“I think [my mother’s training] had a lot of influence on me. She was a teacher, so she wanted me to read books and everything,” my mother-in-law added.

Her mother first introduced her to libraries in Chicago, and she fell in love.

“I thought it was great. Show your card and take a bunch of books home,” she said.

She recalled her parents as readers. The library in her neighborhood had sections of Lithuanian books to cater to the community. Her parents also subscribed to Lithuanian newspapers and magazines. To this day, my mother-in-law still subscribes to one of those newspapers.

Her parents learned to speak English at work and through television.

“We bought a t.v., and we watched as a family on the sofa. We all sat together, ate popcorn, and watched t.v.-- wonderful t.v.--four channels, I think– 2, 5, 7 and 9,” she recounted. “Then when I was growing up, we started to go to the movies together, and then I started to go to the library a lot.”

Technology, then, enhanced the learning of my mother-in-law’s family, but it did not replace the role of reading.

My mother-in-law remembered loving sci-fi and comic books.

“I don’t know if someone gave [a comic book] to me or if my parents bought it in a flea market or something,” she said. “I don’t know, but I was collecting ‘Superman’ books and ‘Wonder Woman’ books– any comic book that I could get my hands on, and I had a whole collection of them. I loved them.”

By the time my mother-in-law finished 8th grade, she was ready for the neighborhood public high school, which was highly rated at the time. She asked her parents to let her attend. They agreed.

“It was the best thing I decided to do,” she said.

She was put in college prep courses and graduated fourth in a class with more than 500 students.

From there, she attended pharmacy school but would leave before graduating to get married and raise children. She returned to pharmacy school at the age of 35 and earned her degree from the University of Illinois’s College of Pharmacy at the age of 40.

She said she had to be motivated to do all that studying as a mother of four. She described how she would attend classes during the day while her children were at school. In the evenings she would pack herself sandwiches and something to drink and then relocate herself to a second property she and her husband owned for rental purposes. She had a desk with a chair and a lamp set up in the furnace/coal room there.

“She went back [to school] because she was a good student in the beginning, and our marriage prohibited her to go back for 15 years,” my father-in-law explained. “After that, we both had a talk and decided [with] her capabilities and so on, she could go back and finish it, and we’d have a better life and financial support.”

He added that her mother had asked him for years to promise her that her daughter would go back to finish her degree. My mother-in-law never knew this.

“[Her parents] were highly educated… Her parents were disciplined and made her disciplined,” my father-in-law noted.

His wife would work as a pharmacist until her retirement at the age of 65, continuing throughout to read for both pleasure and for her continuing education requirements of the profession. Only recently, 15 years into retirement, did she allow her pharmacy license to lapse. She continues to read the pharmacy magazines her pharmacist daughter still brings her, though.

In retirement, she also has helped some of her grandchildren with their Lithuanian homework from the Saturday school they attended.

“[Helping them] helped me, too, because then I got stronger in writing. That’s how I am able to write to a cousin in Lithuania because she does not write in English,” she explained.

Additionally, each grandchild has received two books to help them learn the Lithuanian language. One is a pictorial children’s dictionary called “Richard Scarry Mano Žodynas,” which translates to “My Dictionary.” The other is “Meškiukas Rudnosiukas” by Vytė Nemunėlis. This classic Lithuanian children’s poetry book titled “The Little Brown-Nosed Bear” follows a little bear and his family as they go about their daily activities in the forest.

First published in 1939, “Meškiukas Rudnosiukas” was taught in many of the Lithuanian schools in the States, which is where my in-laws learned of it as children. It’s a story that continues to be told from generation to generation, and my mother-in-law can still recite a good portion of it from memory.

“I like it, and I want the [grandchildren] to like it. Not that I’m pushing it. This is America, but I guess this was a favorite story of mine,” she said as she flipped through the pages, pausing to read some of it in Lithuanian.

My mother-in-law expressed a modest kind of pride that she is fluent in two languages.

While my own child is not, she occasionally asks her father, who is also fluent in both languages, to teach her the language, dragging out the Richard Scarry dictionary for assistance. Sometimes, he will sit with her and read “The Little Brown-Nosed Bear,” which he, too, remembers from Lithuanian Saturday school.

While I hope my child continues to learn her heritage and even another language, my greater hope for her is this: If reading can open up limitless worlds of love, loss, life, legacy, and learning, I hope she hears her motutė’s (or grandmother’s) words whispering in her ear: “How else will you know things if you don’t read?”